Summary of an article describing training cues and coaches’ comments used in Georgian Olympic weightlifting.

Who

6 coaches of Olympic weightlifting athletes aged 12-19 years mostly at the beginning of their weightlifting training (Georgia).

Design

Ethnographic research. Observations were conducted in 2011 and 2012.

Outcome measures

- coaching cues

- coach-athlete relationship

- athlete-athlete relationship

coaching cue – a word or a phrase used by a coach to evoke a certain performance from an athlete.

Main results

Each athlete has a 1:1 relationship with their coach who programs and helps the athlete during the training and competition. Athletes mainly train between 70 and 85% of their 1RM. The role of the coach is to progress the athlete’s ability to lift with restricting unplanned and excessive attempts (to develop proper technique and reduce risk of injury).

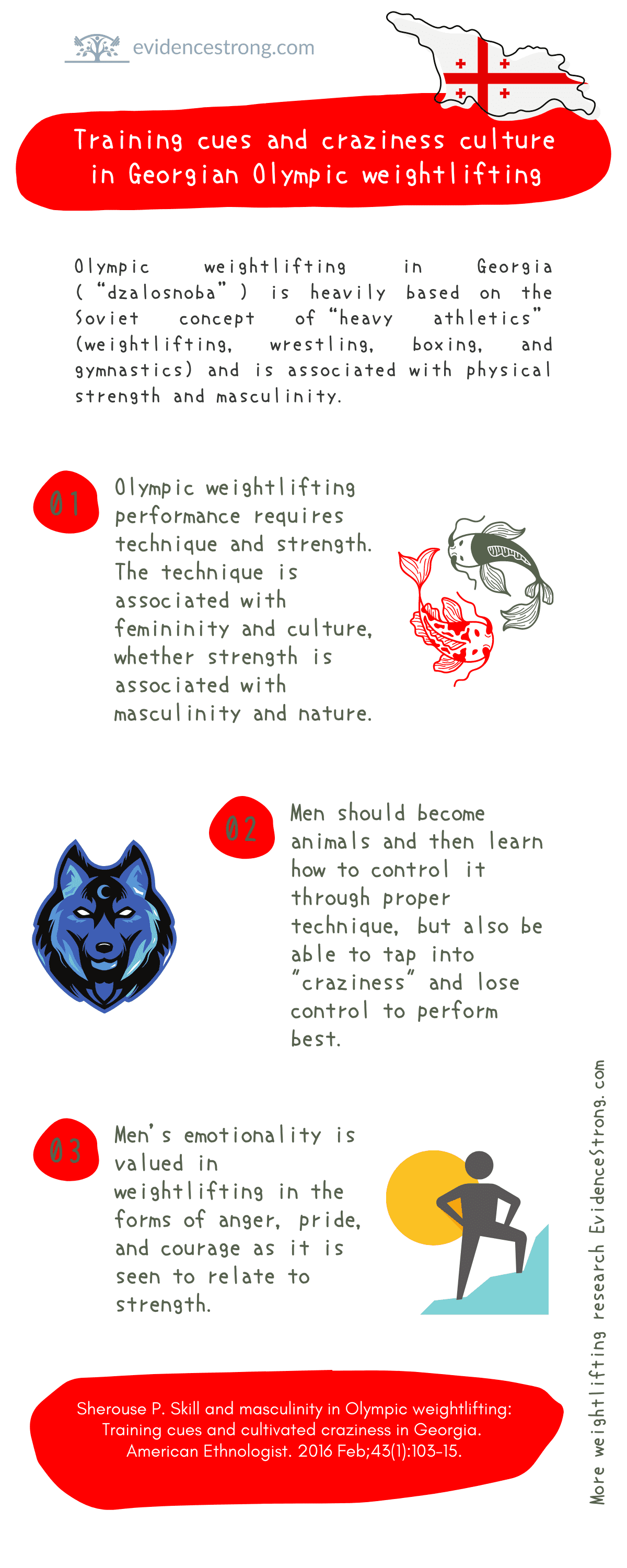

Olympic weightlifting in Georgia (“dzalosnoba”) is heavily based on the Soviet approach in which weightlifting is a part of “heavy athletics” (weightlifting, wrestling, boxing, and gymnastics) and is associated with physical strength and masculinity. Historically, big bodies and associated with strength.

Olympic weightlifting performance requires technique and strength. The technique is associated with femininity and culture, whether strength is associated with masculinity and nature. Men should become animals and then learn how to control it through proper technique, but also be able to tap into “craziness” and lose control to perform best. Men’s emotionality is valued in weightlifting in the forms of anger, pride, and courage as it is seen to relate to strength.

In general, coaches combine and balance cues from both femininity-masculinity, culture-nature, and technique-strength. Although, women are seen as having a great technic and skill (“become better weightlifters”), rather than relying only on strength. Men are often seen as trying to muscle the weight instead of focusing on technique.

Training cues (“Coaches use training cues to ingrain proper movement patterns, elicit embodied states, and emphasize physical positions or proper muscular recruitment.”):

- athletes interpret all cues as evaluations

- the use of cues should allow for the development of how the lifts should “feel” when performed correctly (sensory awareness, proprioception)

- athletes learn not only from the cues directed to them but also from cues, explanations, and criticisms directed at other athletes

- cues are given and received between the athletes according to their social rank/status in the gym (based on the time the person trained for “seriously”), but mainly in the absence of a coach.

- silence is inforced when one is concentrating before the lift, standing and walking in front of the lifter who performs the lift is considered rude

- athlete typically looks at the coach after the lift to receive reaction or correction. The coach may use short or long explanations or demonstrations. Coach controls when the athlete performs the next attempt, tells the athlete to think about technique or to NOT think (just do).

- when the athlete is performing a challenging lift (close or beyond personal best), they usually become a focus of attention of the whole gym. 1

Training cues’ types:

- used by coaches and senior athletes:

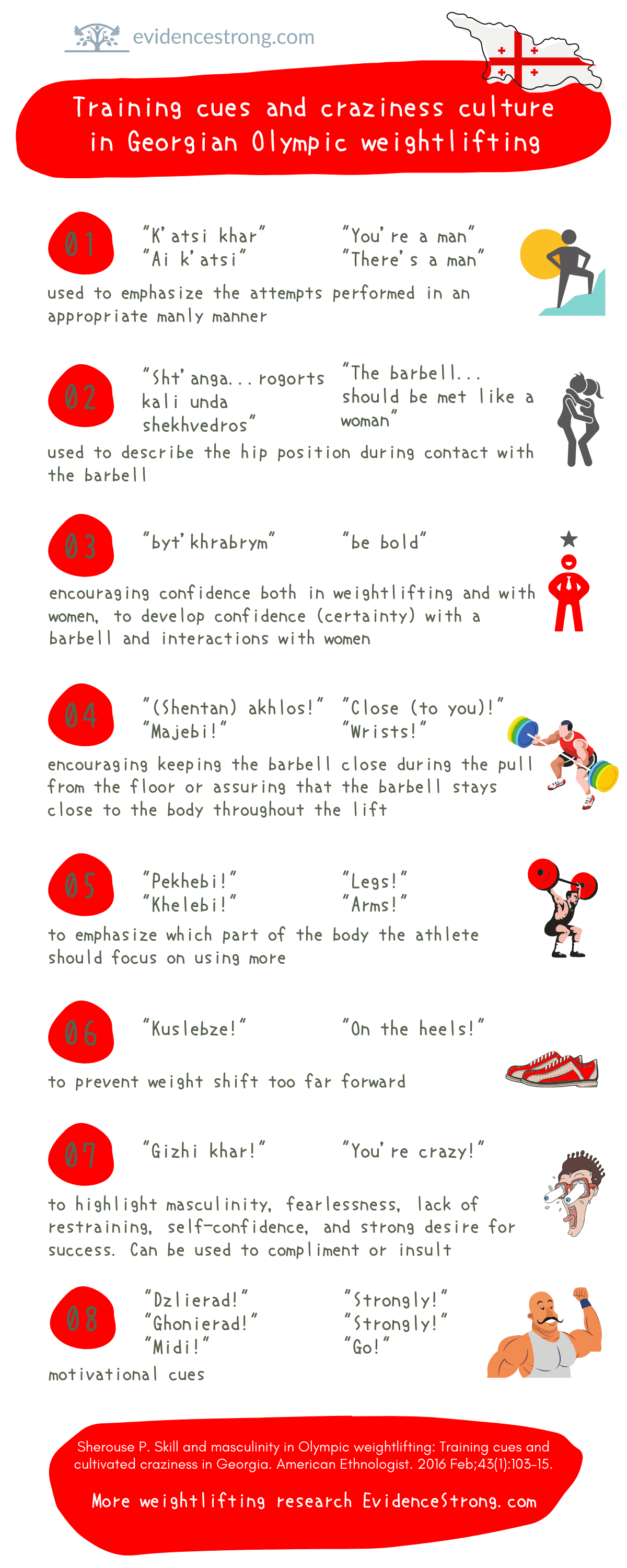

- related to being a man: “You’re a man” / “There’s a man” (“K’atsi khar” / “Ai k’atsi”) - used to emphasize the attempts performed in an appropriate manly manner;

- “The barbell … should be met like a woman” (“Sht’anga … rogorts kali unda shekhvedros”), used to describe the hip position during contact with the barbell

- cues encouraging “be bold” (“byt’ khrabrym”) both in weightlifting and with women, to develop confidence (certainty) with a barbell and interactions with women, develop as a weightlifter and apply the same attributes to interactions with women. But at the same time, not get distracted from training by “chasing girls”

- on keeping the barbell close during the pull from the floor “Close (to you)!” (“(Shentan) akhlos!”) or “Wrists! (“Majebi!”), to assure that the barbell stays close to the body.

- “Legs!” (“Pekhebi!”) and “Arms!” (“Khelebi!”) emphasize which part of the body the athlete should focus on using more.

- “On the heels!” (“Kuslebze!”) to prevent weight shift too far forward

- “You’re crazy!” (“Gizhi khar!”) to highlight masculinity, fearlessness, lack of restraining, self-confidence, and strong desire for success. Can be used to compliment or insult.

- cues positively comparing athletes to animals: “wolf”, “lion”, “deer”

- bodybuilding was encouraged in Georgia, ” Get a pump” (“K’argad ik’achaveb”) after the weightlifting work for the day was completed. Gaining muscle was viewed as positive “Wow, look how big!” (Literally “Wow, what size!”; “Vaime, ramkhela!”). Only discouraged by coaches if excessive and close to the competition.

- used between athletes:

- mainly motivational cues like “Strongly!” (“Dzlierad!”), “Strongly!” (“Ghonierad!”), and “GO!” (“Midi!”).

- senior athletes may occasionally comment on the technique of junior athletes but usually only when the coach is not present

- used by coaches and senior athletes:

Georgian weightlifters although all male, treated female visiting athlete as an equal member of weightlifting community. She was called a “healthy girl” (“janmrteli gogo”), and her squatting technique was admired. She was viewed as a fellow athlete.

Coaches are balancing “craziness” with controlled practice to evoke optimal development and best perfomance. Athletes learn how to channel this “craziness” and control it.

Take home message

Original article

Sherouse P. Skill and masculinity in Olympic weightlifting: Training cues and cultivated craziness in Georgia. American Ethnologist. 2016 Feb;43(1):103-15.

You might want to read next

Best warm-up on power output in Olympic weightlifting

Should you do CORE training before starting Olympic weightlifting?