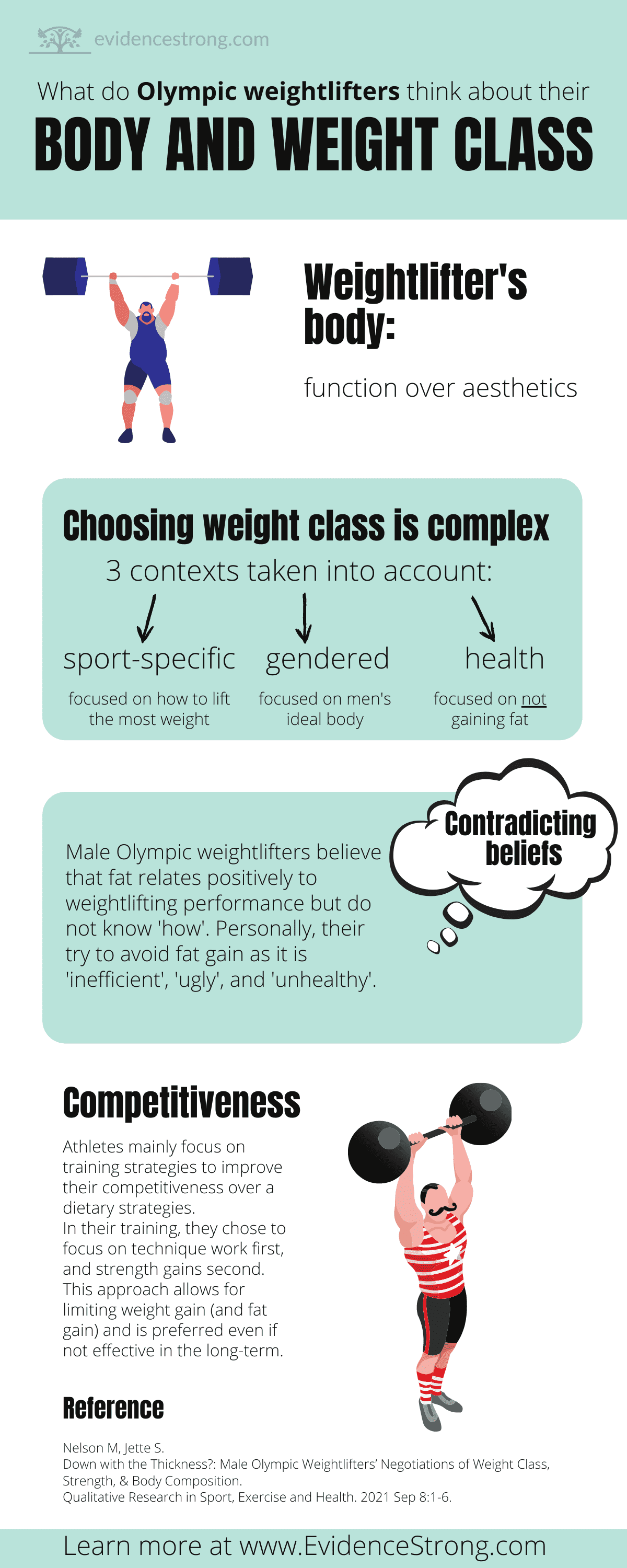

Summary of an article analyzing what male Olympic weightlifters think about their body and how they make decisions on which weight class to compete in.

Who

8 male Olympic weightlifters with experience of at least 4 years (4 to 17 years) and competing in at least 3 competitions at any level (USA). 3 athletes were elite (competed in a World-level competition), 5 recreational (competed at local and/or national level).

Design

In-depth semi-structured interviews.

Outcome measures

Sample questions:

- The first time you thought about competing, how did you feel about the fact that you would have to compete in a particular weight class?

- Have you ever wrestled with being stronger at a heavier bodyweight versus being more competitive but weaker at a lower body weight?

- Do you see a difference between how weightlifters talk about their bodies and how non-weightlifters talk about their bodies?

Main results

- Olympic weightlifting culture: ‘it doesn’t have to look good, it has to work’

- big muscles (thighs, glutes, shoulders, traps, lats) but not like in bodybuilding, the body can be fat, or tall and skinny. Lifting heavy is the most important.

- body depends on the weight class, with lower classes having lower fat percentages all the way to the super heavyweight class where high-fat percentage is desired

- weight standards go up with each weight category.

- weightlifters can move up or down in weight class to optimize their competitiveness.

- moving to a heavier weight class (bulking) allows for strength gain or breaking through performance plateaus. This may come with fat gain and alter biomechanics and speed of the lifting. Requires a long time to match weight gain with strength gain.

- moving down in weight class (cutting) allows for keeping the strength and creating advantage over the athletes who only ever trained in a lower bodyweight class. It can also decrease an athlete’s recovery, muscle mass, and strength.

- each athlete constantly evaluated which weight class is optimal for meeting qualitative standards to the weightlifting competition events.

- variable body composition and focus on functionally of the body did not explain all that went to the decision to compete in a particular weight class.

- many of the lifters did not want to gain weight, especially fat.

- ‘Body fat: theoretically-useful, practicaly-useless’.

- the athletes believed that fat tissue may have a positive effect on the performance of other athletes (i.e., Lasha Talakhadze) but not on their own.

- fat was viewed as “useless fluff”, and as more kilograms to lift. Athletes are worrying about changes in biomechanics and a decrease in speed under the bar which could cause them to miss heavier lifts.

- the idea that body fat is caused by calorie surplus which would also allow for full recovery was not very popular and only voiced by one athlete.

- mostly, athletes were avoiding putting on fat, and therefore putting on weight.

- Male body ideal:

- tension between optimal function (possibly at greater weight) and aesthetics.

- personally, athletes rejected body fat as ugly, but also rejected pursue of visible abs at the expense of the weight lifted. Athletes still experienced a “drive for thinness” taking into account the aesthetics changes while moving up or down the weight class.

- Unhealthy body fat:

- two ways of defining health: 1) performance improvement equals good health regardless of body composition, 2) leanness is a sign of both best performance and health.

- super heavy athletes were facing judgment and pressure to lose weight from the family.

- Body fat was labeled as “unproductive” and “unhealthy”. Athletes wanted to get stronger, but by gaining muscle only and avoiding any fat gain.

- How athletes avoided fat:

- increasing competitiveness focused on strength-building practices rather than a diet. Athletes preferred working on neuromuscular control (technique) over hypertrophy (which would increase body mass and fat).

- athletes tend to think their strength is sufficient but the technique could be improved. In case of failure in competition, lack of technique is blamed rather than lack of strength (even if there was a significant weight cut involved).

Take home message

Original article

Nelson M, Jette S. Down with the Thickness?: Male Olympic Weightlifters’ Negotiations of Weight Class, Strength, & Body Composition. Qualitative Research in Sport, Exercise and Health. 2021 Sep 8:1-6.

You might want to read next

How the month you were born in affects your Olympic weightlifting performance